The Sunshine Coast Dock War

Meet the waterfront millionaires trying to cancel the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

“The Sunshine Coast reality is that 5% of our population have assumed at least 50% of the power in determining how the rest of us live. And they’re abusing it. The shìshàlh have shown a pattern of indifference to our community’s values and residents are justifiably concerned about what lies ahead. This shìshàlh council can’t be blamed for past blunders, but they are responsible for current resentment. And they should be ashamed.”

Brian Lee, editor of the Harbour Spiel, January 2024.

The Pender Harbour and Area Residents Association (PHARA) is a nonprofit, volunteer-run organisation on BC’s Sunshine Coast. Generally, they’re a pretty innocuous group. They host annual trash bashes and ocean cleanups, award volunteers, and maintain a handful of community gardens.

On September 11th, 2024, they took a sharp turn from their usual community-building and submitted a petition to the Supreme Court of BC. Citing “longstanding concerns about the role the province has given the shíshálh Nation in decision-making,” they're demanding that the Province repeal the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA).

At the heart of their beef is the shíshálh swiya Dock Management Plan - an agreement between the Province and shíshálh Nation that regulates the size and location of private docks on the Sunshine Coast.

The BC Assembly of First Nations has responded to their lawsuit, saying that:

“PHARA, and its members who support the Petition, have demonstrated that they value private docks and dock permits over the realization of the fundamental human rights of the shíshálh Nation and all First Nations peoples in BC, a shocking and regressive view that must be directly and vigorously opposed.”

Overturning DRIPA would be a big deal. It was passed in 2019 by a rare unanimous vote in the legislature and "constitutes the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the Indigenous people of the world."1

So far, media coverage of the lawsuit has been sparse. No one’s bothered to ask basic questions like - who’s funding the lawsuit, and what are their motives?

Origins

The devil, who had appeared to sleep throughout all of 1861, began to show himself in 1862.

- Reverend Leon Fouquet, missionary to the shíshálh, in a letter to Reverend Father Superior General Jolivet.2

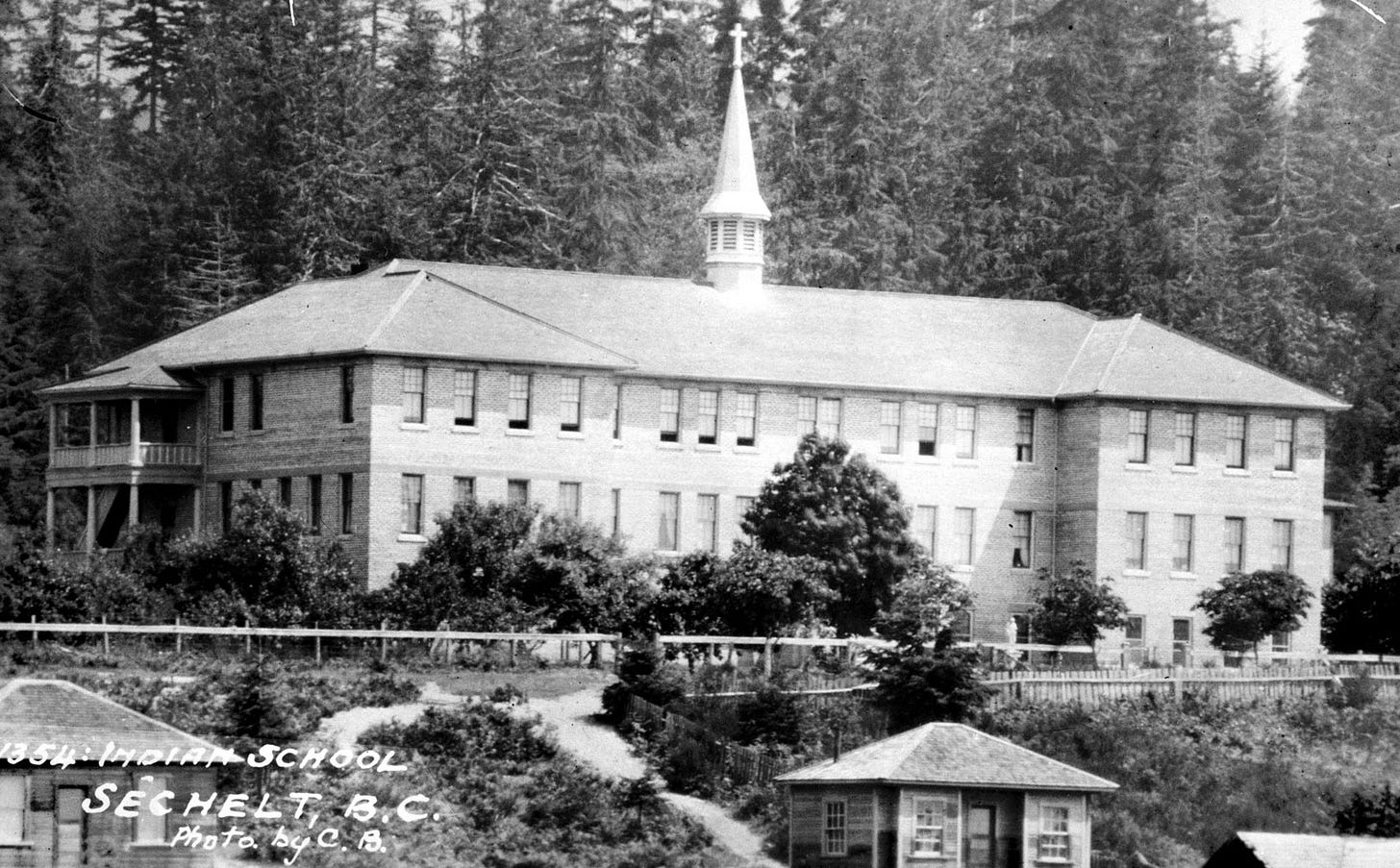

Before Europeans arrived, an estimated 20,000 people lived in shíshálh swiya - a coastal territory just north of Vancouver, stretching from Roberts Creek to Lang Bay.3

Their livelihoods were intertwined with the ocean. Weirs were used to trap migrating siyánxw (salmon) and slháwat’ (herring). In tidal flats, cultivated sea gardens provided an abundance of stl’élum (cockles), sk’áyi (butter clams), smét’áy (horse clams), skw’éts’kw’íts’ (sea urchins), and xéyék (crab).

Two successive waves of smallpox devastated the shíshálh and disrupted their traditional patterns. The first was in 1780, a decade before direct contact with Europeans.

The second outbreak started in Victoria in 1862 and was made much worse by the colonial government's mismanagement. Public hysteria blamed Indigenous encampments for spreading the disease. Newspapers demanded the government "remove the entire Indian population" and bring them "to one of the islands in the Straits—there to rot and die with the loathsome disease which is now destroying the poor wretches at the rate of six each day.”4

Police emptied the camps at gunpoint, burnt them to the ground, and forced some 300 Indigenous people (many of them infected by smallpox) to evacuate back to their home communities.5 Within a year, two-thirds of Indigenous people across BC died. A government census in 1875 found only 175 shíshálh, less than one percent of their population from a century earlier.6

It wasn’t long before Canadians started claiming the land.

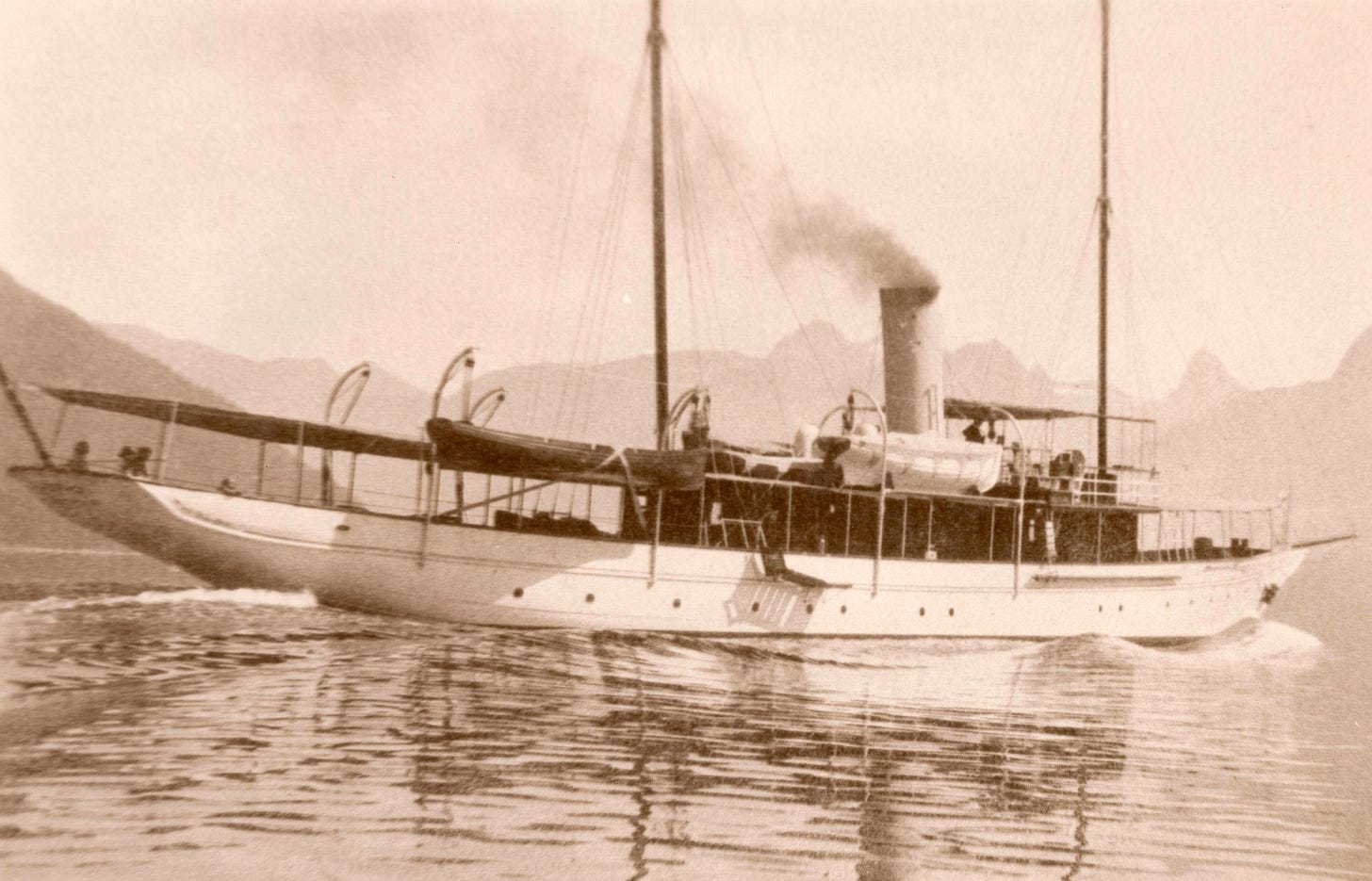

From the get-go, shíshálh villages were coveted by speculators for their value as luxury real estate. In 1892, Herbert Whitaker bought 260 acres in ch'atelích (Sechelt) where he built two hotels and a series of stores, wharves, and rental cottages. The Rogers family, of sugar refinery fame, built vacation homes in kálpilín (Pender Harbour). Seattle aviation executive Thomas Hamilton built a resort for yachters, the Malibu Club, in swiwelát (Princess Louisa Inlet).

But, the shíshálh were still around - an inconvenience to the yachting class. As anthropologist Peter Merchant wrote, “harassing shíshálh families, then burning their homes was the preferred method of pre-emption during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”7 Thirty-six petitions were submitted by the shíshálh to the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs between 1913 and 1916:

When the first white man went there he burned our houses and settled himself there, and so please take this man away and give him another place. (Paul)

Our island in Pender Harbour is only a heap of stones, no water is there and no wood to be had. Now there is a spring on the mainland, about 300 yards away from our island. Now we have used this spring-water for time immemorial, we even had formerly our houses near-by. The white man, that owns the land and the spring now chases our women away, when they want to take water there. Is that right, is that Christian? We cannot use saltwater for cooking and drinking. Please, let us have the use of this water, as our forefathers have had. (Johnson)

Today, shíshálh Band Lands (reserves) cover 0.15% of their territory. The rest is a patchwork of timber leases, Crown land, and private property.

The dock management plan

“The resources of our swiya have sustained our people since time immemorial. We have cared for and stewarded these resources to provide for abundance for our people for many generations. Through development, including dock development, we have seen an incredible decline of these resources. Collectively, we must address the impacts and pressures on the resources to provide for future generations. At the heart of the dock management plan is protection of and restoration of these intertidal resources and cultural belongings.”

-lhe hiwus Joe, Chief of shíshálh Nation

As Canadians continued to settle on the Sunshine Coast, the shíshálh found themselves increasingly hemmed in by private property. In 2005, concerned about their vanishing access to the foreshore, the shíshálh secured a temporary moratorium on new dock permits and entered into negotiations with the Province.

Focusing on the culturally significant village of kálpilín (Pender Harbour), the Province conducted an archaeological survey. It found that “any development in the project area has the potential to destructively impact archaeological materials; with many impacts having already occurred.” An environmental study found that “increased number of docks had adverse effects on algae diversity, kelp cover percentage, fish abundance, and eelgrass presence.”

In 2018, the Province released the Pender Harbour Dock Management Plan (DMP). Its application was limited to kálpilín and only to the foreshore, not private property. Docks were still allowed - so long as they were less than 40 m3 and didn’t block access to the foreshore. Existing dock owners had three to ten years to come into compliance.

Still, this was too much for PHARA. Their spokesperson, Sean McAllister said that “civil disobedience isn’t out of the question.”8 Defiant signs appeared along the coast, declaring “This is our land, not Sechelt land” and “Our marine assets will not be given up without a fight.” A pamphlet called the Pender Patriot circulated, complaining “that the playing field will no longer be level and there will be different rules based on race."9

The Province received over 1700 letters of concern from the community.10 Nearly all of them mention property value:

The enforced removal of private boat houses and docks, as stipulated by the proposed plan, will not only significantly devalue our property but also strip away the very essence of our family's lakeside living experience. These docks and boat houses are more than mere structures; they are integral to our way of life, facilitating countless family activities and memories formed over generations

It’s wrong for people who own or have purchased property in good faith to have their rights, traditional practices, and property values diminished due to DMP.

People that don’t even live here, have never paid taxes, now have the say in how our paradise is run. Pender Harbour has always been known to be a place to live as very special. Our property value now has gone downhill, boaters have been envious of our special place, don’t even wish to drop in for visits!

It’s worth noting that the average value of a waterfront home with a dock on the Sunshine Coast is $1.7 million. The DMP is expected to reduce some property values by 15 to 35 percent - by comparison, property values across BC have increased over 200 percent since 2010.11

Disregarding the public’s concerns, the Province went ahead with enforcement of the new rules. In 2022, sixteen landowners received notice to remove their nonconforming docks. The next summer, government contractors removed the remaining docks under the supervision of an RCMP escort.12

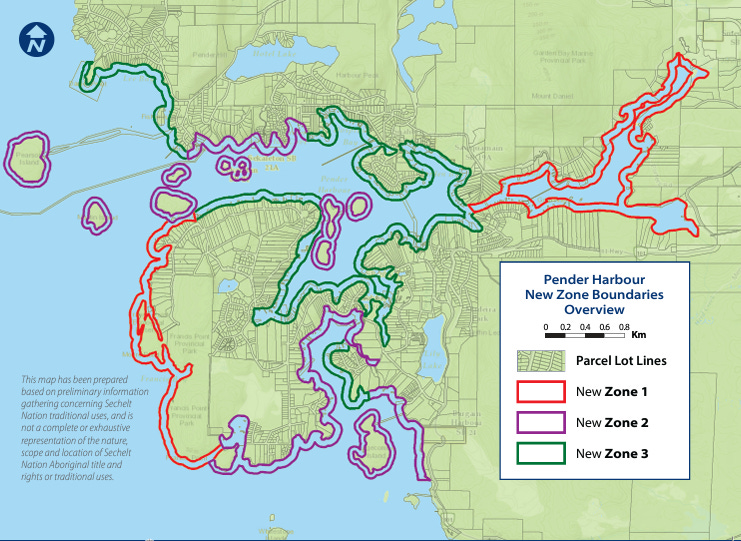

In 2023, the Province upped the ante with a draft amendment, renamed the shíshálh swiya Dock Management Plan, that expanded the plan’s reach to include all of shìshàlh Nation’s traditional territory.

Significantly, the shìshàlh are still negotiating an agreement under DRIPA that may give them, rather than the Province, authority over dock permits on Crown land.13

The lawsuit

PHARA wants to make sure that doesn’t happen. In September 2024, they filed their petition to the Supreme Court of BC. They make two basic arguments:

DRIPA conflicts with section 35 of the Constitution Act.

Indigenous governing bodies shouldn’t have decision-making authority over non-Indigenous persons.

It’s hard to imagine the courts will agree. The federal government, in its own UNDRIP legislation, is clear that:

“The protection of Aboriginal and treaty rights — recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 — is an underlying principle and value of the Constitution of Canada, and Canadian courts have stated that such rights are not frozen and are capable of evolution and growth.”

Their second point is an embarrassing double standard. Non-Indigenous governments have been claiming decision-making authority over Indigenous people since day one. It also goes against the precedent set in court by Haida (2004), Tsilhqotʼin (2014), and most recently Wolastoqey (2024).

To argue their case, PHARA has retained some big-shot lawyers - Robin Junger and Joan Young. Robin, a Harvard Law School graduate, has served as the Deputy Minister of Energy, Mines & Petroleum Resources, and as Chair of the Oil and Gas Commission.

No doubt, the lawsuit’s gonna be expensive. How is a small-town, volunteer-run nonprofit paying for it?

Turns out, that’s a surprisingly hard question to answer. Nonprofits aren’t obligated to disclose their funding and PHARA is a black box. Their website claims they draw their “main funding from a $30 membership per family per year,” but they also solicit donations for a litigation fund. I emailed to ask which individuals or organisations have contributed, but they declined to comment.

But, there are clues. For example, their president, Peter Robson is the editor of Cottage Life West and Pacific Yachting magazines, as well as the author of Pender Harbour Landing: History With a View - a book he describes as a “project to promote Pender Harbour Landing estate properties.”14

Waterfront Protection Coalition

PHARA isn’t the only group simping for yachters on the Sunshine Coast. The Waterfront Protection Coalition was founded shortly after the DMP was released. Their goal is to “advocate for all waterfront communities in Canada who face similar unfair legislation without representation.”

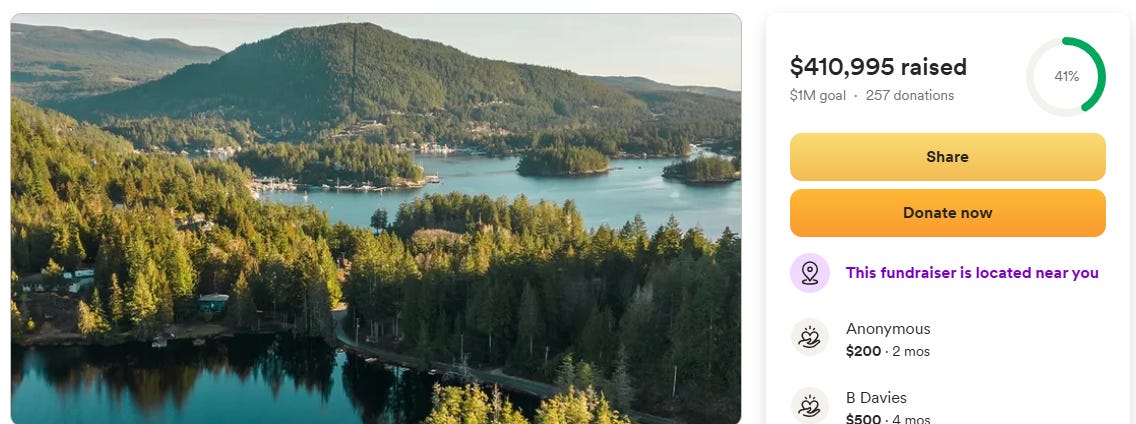

They’ve got money. Their GoFundMe raised $100,000 in its first six days and is currently shy of a half million. Most of the donations are anonymous sums of $10,000 to $25,000.

They’ve hired a PR firm and a lawyer. Their lawyer, Roy Millen’s past clients include: LNG Canada, Denison Mines, Seabridge Gold, Arctic Canadian Diamond, and Pure Gold Mining.

One of their directors is Jim Stewart, a Nanaimo-based realtor. Previously, he served as Director of the BC Liberal Party (under Gordon Campbell, 1999–2012), president of the Vancouver Island Real Estate Board (2011-13), and president of the BC Real Estate Association (2017-19).

But their president, Denise Brynelsen, is the cherry on top of a greasy cake. A Sechelt-based realtor, Denise was the subject of a recent BC Financial Services Authority investigation. In October 2024, they found she had “committed professional misconduct” and ordered her to pay a $100,000 fine, $2,500 in enforcement expenses, and take a remedial education course.

The scandal is juicy. It reveals not only Denise’s stake in denying the DMP but, more broadly, the stake of the luxury real estate industry as a whole in denying Indigenous governance across British Columbia.

In 2017, Denise acted as a dual agent, representing the buyer and seller of a property in Pender Harbour. Her listing described it as an:

“Absolutely one of a kind low-bank waterfront property with private moorage. The completely renovated beach cottage sits right above the shore and faces South with sunshine all day and gorgeous ocean views. Outside you can keep your boat at the private 50’ dock with protected, year round deep water moorage & explore the 2.44 acres of wilderness & privacy.”

What the listing didn’t reveal, is the fact that the foreshore tenure had expired and the “completely renovated beach cabin” was an illegal structure. This was a deliberate omission. Before posting the listing, Denise had received an email from the Province clarifying that:

“the cabin is currently not legalized and the use is non-conforming to our policies. Given that the dock management plan is not final yet, I can’t say for certain if we could legalize it after the plan comes into effect. However, generally speaking such a use on Crown foreshore is contrary to provincial policies and likely would not be approved.” (emphasis in original)

Without disclosing this information to her clients, in September 2017 Denise sold the property for $900,000.

Within a year, the new owners received a letter from the Province demanding they remove their cabin from the foreshore. They tried relocating it inland but discovered that it had been renovated illegally and would have to be brought to code before they could move it. In 2021, they decided to demolish the cabin at their own expense, and have a new house built on the property.

Denise gambled that the DMP would be toothless - that she could sell an illegal dock and cabin to unsuspecting buyers and the Province wouldn’t do anything about it. Proven wrong, she’s become a martyr and leader in the fight for waterfront property values.

It’s realtors all the way up

In 2023, real estate contributed over $56 billion to the provincial economy—more than three times as much as mining, oil and gas, agriculture, fishing, hunting, and forestry combined.15 Powerful interests are at play.

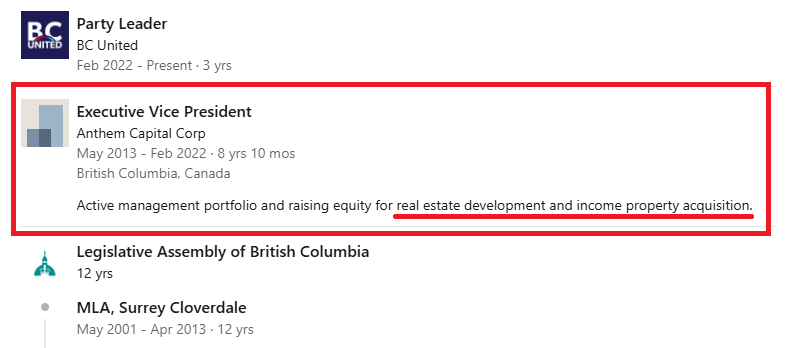

Leading up to the 2024 provincial election, Kevin Falcon was the leader of BC United (formerly BC Liberals) and a probable candidate for Premier. Previously, he’d spent a decade as Vice President of Anthem Capital, a multinational corporate landlord that uses artificial intelligence to manage their properties and “maximize quarterly distributions to investors.”16

A few months before the election, he posted a video on Facebook claiming that the DMP threatened private property rights across the province and must be stopped.

The next day, his party announced Sechelt realtor Chris Moore as their candidate for the Powell River-Sunshine Coast riding. Chris is a member of both the President’s (RE/ MAX - Top 1%) and Chairman’s (Royal LePage: $500K-$1M) Clubs for top producers and, if elected as MLA, one of his “five bold missions” was to overhaul the DMP.

Even John Rustad, leader of the BC Conservatives, got in on the fun - promising to “stop the NDPs assault on land rights and repeal UNDRIP,” calling it “an assault on your private property rights and our shared rights to use Crown Land.”17

Chip

Clearly, there are a lot of rich people who aren’t okay with Indigenous people telling them how big their docks can be.

But there’s one billionaire real estate mogul in particular who has the money, motivation, and such a specific, personal vendetta that it’s nearly impossible to imagine he isn’t involved.

Chip Wilson is best known as the founder of Lululemon, but in 2015 he was pushed off the board for his offensive comments about women.18 Since then, he’s pivoted into real estate and development.

His new company, Low Tide Property, is on a mission to build a real estate portfolio worth $1.5 billion by 2030.19 They’ve been bullish, buying up property in East Vancouver neighbourhoods. Their strategy is to evict low-income tenants, charities, musicians, and artists - then turn their homes into revenue-generating condos and storefronts.

At the same time, Chip got political. With a $380,000 donation, he founded the Pacific Prosperity Network, a right-wing lobby group. They own the Facebook page BC Proud and use it to get around Election BC’s third-party advertiser laws since - even though they’ve bought followers - social media posts don’t count as advertisements.20 They campaigned for both Kevin Falcon and John Rustad.

Chip was also a major force behind developer-friendly Ken Sims getting elected Mayor of Vancouver.21 In return, Ken named October 3rd the city’s official Chip Wilson Day.

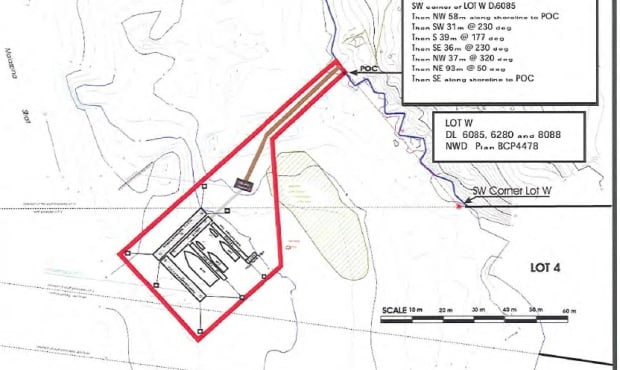

Chip’s involvement with the DMP started in 2013 when he submitted a dock proposal for his $9 million vacation home in Middlepoint Bight, halfway between Pender Harbour and Sechelt. The proposed dock was 2,498 ft2 - big enough for the seasonal moorage of his two 24-foot boats, 47-foot yacht, and various small watercraft. The proposal also included two 3,106 ft2 breakwaters.

His neighbours were pissed. Unhappy about the prospect of losing their swimming zone and worried about the impacts on eelgrass meadows and bird habitat, they wrote letters of concern to the district. The council unanimously opposed the project.22 shíshálh Chief Calvin Craigan demanded consultation, saying "If this fella [Chip] is planning on building a dock, he has to approach the Sechelt band.”23 It made headlines across the province.

Trolling the haters, for April Fools 2015 Chip put up a fake development notice in front of his Vancouver mansion. It proposed building an obnoxiously large, 8000 square-foot heliport dock off his backyard into English Bay.

In the end, neither the shíshálh nor the regional district could stop Chip from building his dock. The DMP was still in development and only the Province had decision-making authority over the foreshore. After moving the dock 20 meters to avoid an eelgrass bed, it was approved in 2017.

Eight years later, and Chip could be forced to demolish his dock. One of PHARA’s main grievances with the DMP is that it doesn’t allow for the grandfathering of existing docks.24

It’s a class war, not a race war

Nearly everyone involved in the fight to cancel DRIPA is a realtor, a yacht owner, or both.

To advance their interests, they’re working hard to stoke the flames of centuries-old racial tensions on the Sunshine Coast. They want us to believe they’re the good guys, standing up against Indigenous rights on behalf of all Canadians.

Because, as long as we’re worked up about Indigenous people coming after our rights, we won’t notice that it’s the yachting class who are taking them away. That it’s their oversized docks blocking our access to public land, their obsession with property values fueling our housing crisis, their yachts guzzling gas and polluting our water, and their excessive wealth going toward a hateful lawsuit rather than literally anything else.

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. UBC Indigenous Foundations.

quoted in: As far as the eye can see : the shíshálh in their territory, 1791-1920. Peter Merchant. 2020.

quoted in: The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline Among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. Robert T. Boyd 1999

“When reading these numbers, caution should be taken, as many shíshálh avoided either census, choosing to remain in the distant reaches of tems swiya, thereby reducing the recorded numbers. Regardless, the low numbers suggest that thirteen years after this second smallpox outbreak, shíshálh population remained perilously low.” As far as the eye can see : the shíshálh in their territory, 1791-1920. Peter Merchant. 2020.

ibid.

Working group not giving up on dock plan changes. Coast Reporter. 2018

Tensions rise in Pender Harbour over outlawed new docks. Globe and Mail. 2015

Proactive Disclosure (PDF, 66.8MB)

DMP Financial Impact Assessment. The Waterfront Protection Coalition. 2024

Harbour Spiel. January 2024

Order in Council 2022-444. Province of BC

From Peter Robson’s personal website

BC’s GDP By Industry: 2023. Government of BC. 2024

From Anthem Capital’s website: “By leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, and software as a service (SAAS) technology, we increase automation and productivity, streamline operations, mitigate risk, and decrease expenses. This maximizes your quarterly earnings and total returns when the asset is sold.”

Memo from the director of asset management - Low Tide Property.

Right-wing populist group fined for ads targeting left-leaning politicians. Canada’s National Observer. 2022.

The Billionaire and the Mayor. The Tyee. 2022

Lululemon founder’s dock proposal has neighbours up in arms. Times Colonist. 2015.

B.C.'s Sechelt Indian Band demands consultation over Lululemon founder’s dock plans. Globe and Mail. 2015

It is regrettable that the Dock Management Plan (DMP) was poorly written and inadequately structured. Its simplistic, one-size-fits-all approach to dock sizes fails to account for the varying characteristics of property sizes, foreshore lengths, and habitat conditions. A more rigorous, science-based methodology should have been employed, with dock size tailored to the specific foreshore dimensions— for instance, smaller foreshores could accommodate smaller docks, while larger foreshores could support larger ones. This approach mirrors the widely accepted "square footage ratio" used in other private property construction practices.

Furthermore, the DMP’s disregard for the specific marine habitats surrounding individual docks is concerning. This omission underscores the plan's lack of grounding in scientific research, despite its claims to the contrary. The relevant scientific data has yet to be shared with the community, which undermines the credibility of the plan. Additionally, the same science is being applied to both marine and freshwater environments, which, given their distinctly different ecologies and habitats, further highlights the flaws in this approach.

In light of these significant issues, the DMP appears to be a generic, one-size-fits-all policy imposed by an authority with questionable motivations, cloaked under the guise of environmentalism.

Maybe the First Nation should lead by example by removing the deep sea dock and gravel conveyor from their huge open pit operations, that they intend to expand after clear-cutting the adjacent land last year.