“Land prices are high, it is said, higher than anything would warrant. ‘Why, the workingmen cannot afford to pay at the rate demanded for these tiny outside lots,’ asserted one man recently. The same thing was said here twenty years ago, answer the pioneers; others of us know that it was repeated ten years ago and five years ago, and our children and our children’s children will hear the same tale of woe decades hence.”

- R McDougal, BC Real Estate, 1911.

It’s no secret that housing keeps getting more expensive. But, depending on who you ask, you’ll get a different answer why.

One thing’s for sure - there’s big money at play. Real estate is British Columbia’s biggest industry. In 2023, it contributed over $56 billion to the provincial economy. That’s more than three times as much as mining, oil and gas, agriculture, fishing, hunting, and forestry combined.1

Rich people love buying property. All of the ten wealthiest families in BC have substantial investments in real estate and development. For many of them, it’s their main business.2

But, housing is also a basic human right, a fact at odds with our profit-driven industry.

This essay is an exploration of two questions:

Why does rent keep going up?

How have tenants fought back?

Enclosure

“Those that buy and sell land, and are landlords, have got it either by oppression, or murther, or theft; and all landlords lives in the breach of the Seventh and Eighth Commandements, thous shalt not steal, nor kill.”

Gerard Winstanley, 1649.

If we’re going to understand British Columbia’s housing crisis, we need to start with Britain. After all, that’s where our laws come from, and their king is the province’s biggest landlord.

Private property hasn’t always existed. In medieval England, nearly half of the land was owned collectively, through a system known as the commons.

Lords managed big rural estates and collected rent from their tenants. But they didn’t own the land outright. Their tenants, commoners, had the right to farm, graze animals, collect wood, hunt, and fish where they wanted.

For Lords, the commons were a burden. Commoners lived off the land, only worked a few days per week, and couldn’t pay much rent.3

By the 13th century, wool had become “the backbone and driving force in the English medieval economy.”4 Raising sheep was lucrative, but it took a lot of land. If the Lords could turn the commons into pasture, they could make some serious coin.

They petitioned the King, arguing the commons were primitive and a waste of valuable land. Without a profit motive, the commoners were deadbeats. If industrious, forward-looking guys like themselves could make the land more profitable, the commoners shouldn’t be allowed to stop them! As the “father of liberalism,” John Locke put it:

“God gave the world to men in common; but it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated… as much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of, so much is his property. He by his labour does, as it were, inclose it from the common.”

In 1235, the King allowed the Lords to seize the commons and claim it as their own in the Statute of Merton. It began with the line: “Because many great men of England have complained that they cannot make their profit…”

The only condition was that the Lords leave the commoners “sufficient pasture.”5

So began a process known as enclosure. Landlords built fences around the best land and, slowly, pasture by pasture, the commons became their exclusive property.

The rule about leaving their tenants “sufficient pasture” was either forgotten or ignored.

In 1516, Thomas More described how landlords “enclose all into pastures, they throw down houses, they pluck down towns, and leave nothing standing, but only the church to be made a sheephouse.” Homelessness was a problem. A survey of Norwich in 1571 found that “many of the citizens were annoyed that the city was so full with poor people, both men women and children, to the number of 2,300 persons, who went from door to door begging.”6

Rather than rein in the increasingly powerful landlords, the government banned being poor. In 1536 Parliament passed An Act for Punishment of Sturdy Vagabonds and Beggars:

“A valiant beggar, or sturdy vagabond, shall at the first time be whipped, and sent to the place where he was born… if he continue his roguish life, he shall have the upper part of the gristle of his right ear cut off; and if after that he be taken wandering in idleness, or doth not apply to his labour, or is not in service with any master, he shall be adjudged and executed as a felon.”7

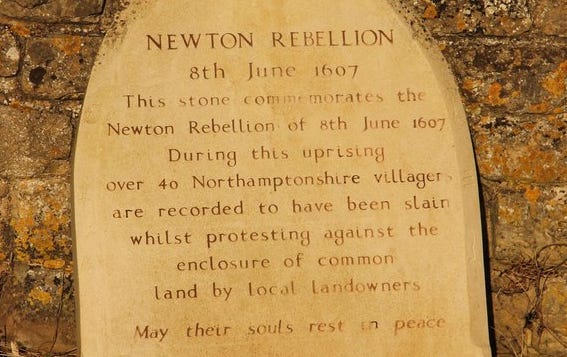

As you can imagine, the commoners were not chill about this. There were endless enclosure riots, the era’s “pre-eminent form” of protest.8 Notably, Kett's Rebellion (1549), the Midland Revolt (1604), Newton Rebellion (1607), and the Western Rising (1626-32).

The coolest resistance was the Diggers, a radical pacifist sect of Christian weirdos. They agitated for a return of the commons in 1649, more than four hundred years after the Statute of Merton. By then, some landlords had started to forget where their property came from. In a series of pamphlets, the Diggers dished out a heavy reminder that:

“The power of enclosing land and owning property was brought into the creation by your ancestors by the sword; which first did murder their fellow creatures, men, and after plunder or steal away their land, and left this land successively to you, their children. And therefore, though you did not kill or thieve, yet you hold that cursed thing in your hand by the power of the sword; and so you justify the wicked deeds of your fathers, and that sin of your fathers shall be visited upon the head of you and your children to the third and fourth generation, and longer too, till your bloody and thieving power be rooted out of the land.”9

Having learned from the earlier failures of armed rebellion, they opted for a strategy of nonviolence.

They occupied private pasture on St George’s Hill, started farming, and invited anyone to join and share in the harvest. But the landlords weren’t having it. They hired thugs to beat up the Diggers and burn down their communal houses. When that didn’t work, they brought them to court. The court charged them with being sex freaks and threatened to bring in the army.10 Within the year, their occupation was abandoned.

Thanks to landlords, St George’s Hill is now one of the most exclusive gated communities in the world. It’s got a nice golf course and the average property costs over £5.5 million.

Clearances

“As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce. The wood of the forest, the grass of the field, and all the natural fruits of the earth, which, when land was in common, cost the labourer only the trouble of gathering them, come, even to him, to have an additional price fixed upon them. He must then pay for the licence to gather them, and must give up to the landlord a portion of what his labour either collects or produces.”

- Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776. Even the Grandaddy of capitalism hated landlords.

By the end of the 1700s, almost all of the commons in England had been enclosed. English landlords, stupid rich, started looking abroad for more land.

In Scotland, they ran a program of mass eviction known as the Highland Clearances. Commons became private pasture, clansmen became tenants. To make room for more sheep, the government encouraged (often forcibly) mass emigration to the colonies. That’s how some 170,000 Scots ended up in Canada.11

In Ireland, it was a similar story. Between 1850 and 1870, English landlords extracted over £34 billion in rent, mostly from poor tenant farmers.12 Even in the thick of the Great Potato Famine, they didn’t ease up. If you couldn’t afford rent, it was either starve or off to the colonies. A million starved and two million fled. By 1871, the Irish had become the largest minority group in nearly every Canadian city and town.13

But, neither Irish nor Scottish tenants were passive victims of English landlords. One powerful strategy of resistance that Irish tenants invented was the boycott.

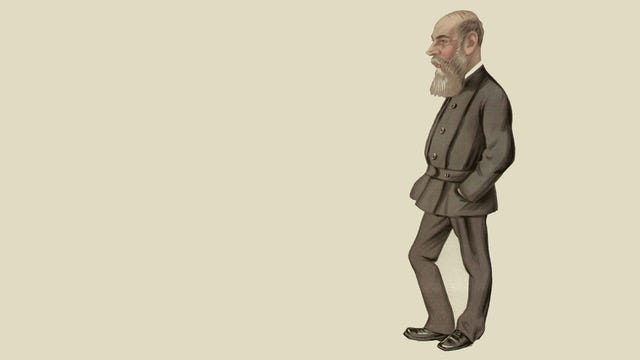

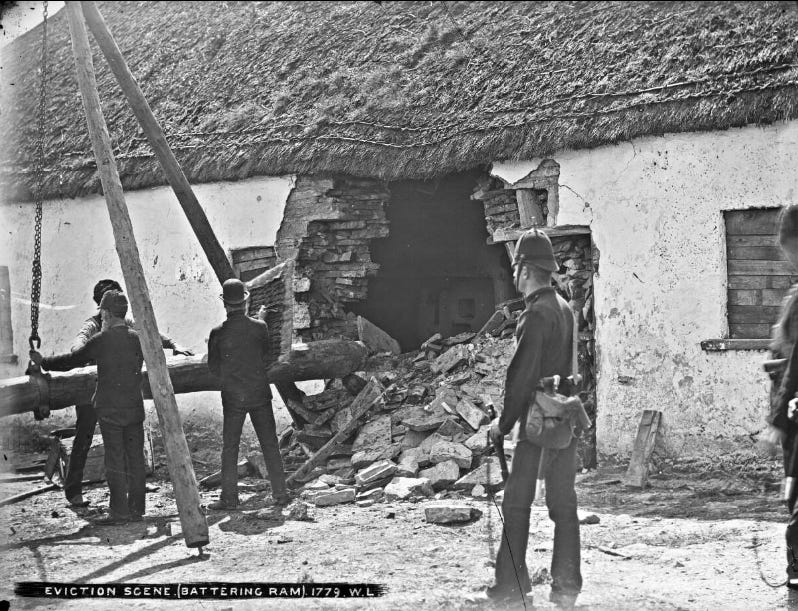

Captain Charles Boycott was an English land agent for Lord Erne, a wealthy absentee landlord who owned 40,386 acres of land in West Ireland. In the fall of 1880, some of Lord Erne’s tenants asked for a reduction in rent because of the year’s bad harvest, but Boycott refused. Instead, he applied to evict eleven of them - including a feisty Mrs. Fitzmorris.14

When seventeen cops showed up to serve Fitzmorris her eviction notice, the neighbourhood women were ready. They pelted the cops with stones, mud, and manure, driving them away.

News about the botched eviction spread and members of the Irish Land League gathered around Boycott’s estate. They were itching to try out their new strategy of “social ostracism” against the English landlords and thought Boycott might be their guy. They convinced his servants and farmhands to quit. Soon, shops in the nearby town refused to serve him too. It was harvest season, and no one was willing to help Boycott with his crops.

Other landlords, worried they might be the Land League’s next victims, fundraised to bring in farm workers from out of province. The Irish government sent close to a thousand troops to escort them. Boycott lost £6,000 of his own money and the operation cost the government another £10,000 - "one shilling for every turnip dug from Boycott's land.”15

Aside from being an expensive hassle for landlords, the boycott was a media sensation. The phrase (and tactic) spread around the globe, strengthened the power of the Irish Land League, and galvanized resistance to English landlords.

British Columbia

"In the beginning, all the world was America… [and] the wild Indian, who knows no enclosure, is still a tenant in common.”

John Locke, 1690.

Having consumed Ireland and Scotland, enclosure started to spread across the Colony of British Columbia in the second half of the 1800s.

Many of BC’s early settlers were tenants, displaced from their European homes by landlords. They were Irish, Scottish, English, and they wanted what they’d been denied in their homelands - land.

Unfortunately for them, BC was already occupied.

They petitioned the King, arguing Indigenous people were primitive and wasted valuable land. Without a profit motive, they were deadbeats. If industrious, forward-looking guys like themselves could make the land more profitable, Indigenous people shouldn’t be allowed to stop them! As BC’s second premier put it:

“Shall we allow a few red vagrants to prevent forever industrious settlers from settling on the unoccupied lands? Not at all… Locate reservations for them on which to earn their own living, and if they trespass on white settlers punish them severely. A few lessons would soon enable them to form a correct estimation of their own inferiority.”16

In 1858, the discovery of gold in Tsilhqot'in territory added fuel to the fire. Suddenly, the isolated territory—essentially untouched by European settlers until then —was flooded by speculators staking their claims in BC’s biggest gold rush, the Cariboo.

Practically overnight, the land was transformed into a grid of private property. Rivers were dredged, run through troughs, pumped full of mercury, the gold extracted. Forests fell. Boomtowns boomed.

In 1862, a smallpox epidemic broke out. Within months, two-thirds of the Tsilhqot'in died. There’s compelling evidence that settlers spread the disease intentionally to clear the land.17

In 1863, wealthy Victoria landlord Alfred Waddington started building a road to open the goldfields to the coast.18 For the Tsilhqot’in, this was the final straw. They declared war against the settlers and, in a series of attacks, killed nineteen. In response, the Province sent in the army. The first expedition got lost, and the second was ambushed by Tsilhqot’in warriors and forced to retreat.

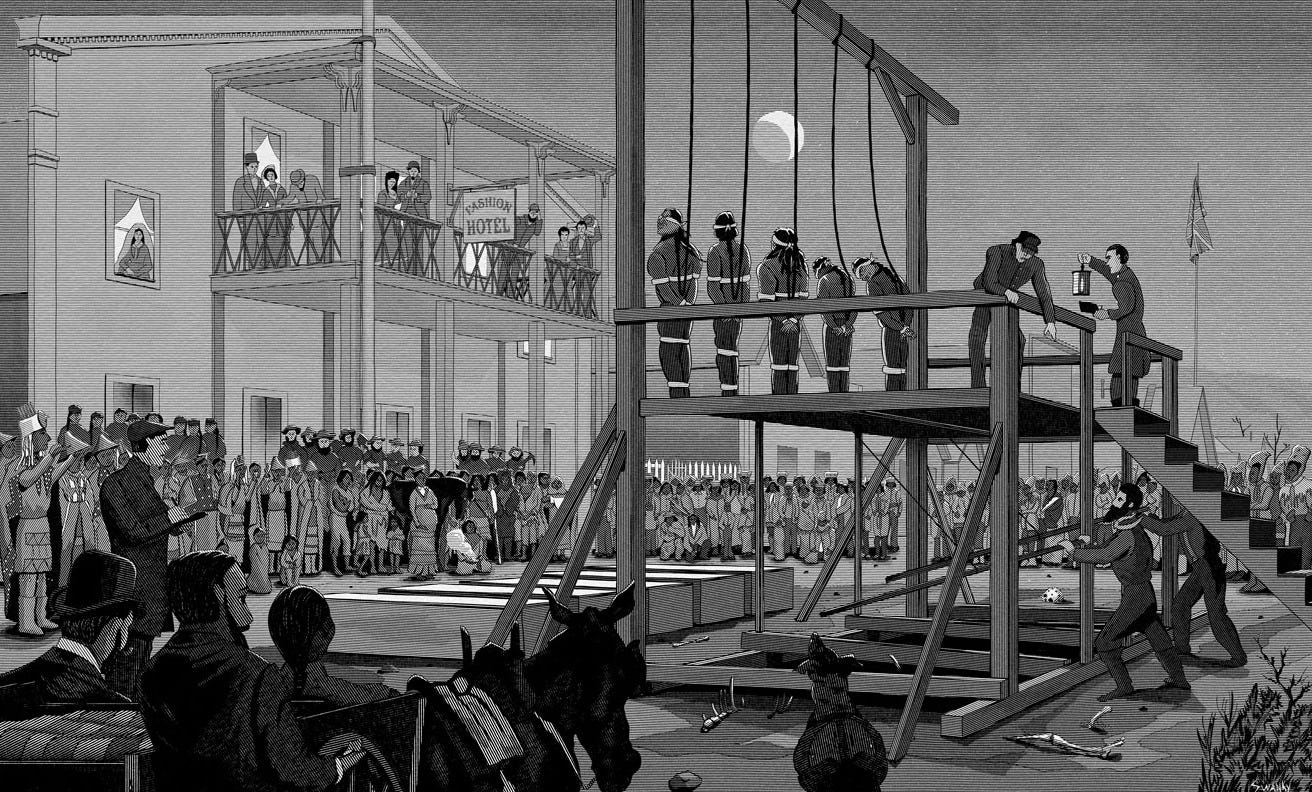

Unable to beat them in war, the Province invited the Tsilhqot’in to Quesnel for peace talks. When the Chiefs showed up, they charged them with murder - five were found guilty and hanged.19

But, in the long run, it turns out war is a pretty good way to keep the landlords out.

In the 2014 ruling, Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, the Supreme Court acknowledged that the Tsilhqot’in never ceded their land and recognized their title to 1700 km² of Crown land. It was the first time the Province recognized any Indigenous Nation’s title.

Strategically, the Tsilhqot’in decided not to claim any private property in their title case. The right to get rich off real estate is a sacred English value they weren’t ready to challenge.

Still, some landlords are worried Indigenous rights have gone too far and might be coming after their property next. In 2016, the Province assured landlords they have nothing to worry about - the “government must and will always defend, with conviction, the sanctity of private land and private land rights.”20

… to be continued in part two where we talk about the time World War Two veterans took over the Hotel Vancouver and other shenanigans.

BC’s GDP By Industry: 2023. Government of BC. 2024

Whose wealth is it anyway? BC’s top 10 billionaires and the rest of us Alex Hemingway and David Macdonald. 2018

Medieval peasants actually had a pretty chill work-life balance. They worked as little as 120 days per year, had all kinds of holidays, and generally more leisure time than we do today. The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. Juliet B. Schor. 1991

History of the Wool Trade. Ben Johnson. 2015

Urban Enclosure Riots: Risings of the Commons in English Towns, 1480–1525. Christian D. Liddy. Past & Present, Volume 226, Issue 1, February 2015, Pages 41–77

A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England, Gerrard Winstanley, 1649

Specifically, they were accused of being sexually liberal Ranters - an accusation they denied. Vann, Richard T. "The Later Life of Gerrard Winstanley". Journal of the History of Ideas.

Scottish Canadians Canadian Encyclopedia

(adjusted for inflation), (Vaughan, William Edward (1994). Landlords and Tenants in Mid-Victorian Ireland.)

(with the exception of Quebec) Canadian Encyclopedia: Irish

Marlow, Joyce (1973). Captain Boycott and the Irish pp. 133–142

Boycott, Charles Cunningham Dictionary of Irish Biography

Daily Colonist. March 8, 1861. Amor De Cosmos

How a smallpox epidemic forged modern British Columbia Joshua Ostroff. Maclean’s 2017

Waddington Alley: A 1908 Street Experience

Alfred Waddington purchased three lots in 1858, constructed a private alley to enhance their value and quickly erected wooden buildings to rent. It was a shrewd maneuver. The British Colonist reported Waddington’s income from shop rentals in 1860 was $1000 a month, an astounding sum at the time. Often called “Victoria’s original shopping mall,” alley businesses included a livery stable, bakery, blacksmith, restaurant, fishmarket, shoemaker, gambling establishment, dancehall and bowling alley.

We Meant War, Not Murder! Gord Hill and Sean Carleton.

Province files response to First Nations title claim BC Government 2016 (emphasis added)